Swan Song

A final edition and a goodbye.

Good afternoon!

Dear reader,

Last year, I joined The Signal, excited to write stories that dig deep into the complicated and ever-mutating business of media. The Impression was originally intended to be a newsletter on the creator economy. Eventually, it became your weekly primer on the business of films, streaming, music, news, social media, advertising, and everything else that holds this fascinating media monster together.

As I hand over The Impression to the folks at The Core, I am signing off. This is my last edition.

In these 65 editions and 16 months, The Impression swelled to over 8,000 subscribers. It covered some of the biggest stories shaping media in India – the Sony-Zee deal, the fate of Disney-Star, the post-merger struggles of PVR-Inox, the unstable future of streaming and news, and the technologies changing the way we are entertained and informed.

I had the privilege of meeting several readers of The Impression during this time. Many of those conversations inspired new ideas and made stories in The Impression richer.

Thank you everyone for being part of the ride!

On to the final edition.

Money, Morals, and Indian Media

If you’re running any media business right now, you probably already know this is a trying time. Even leaders in India’s entertainment, social media, news, and other media businesses are struggling to figure out how to make money. Customer preferences are constantly changing but none seem to tend towards paying for content. As a result, the industry is going through a wave of consolidation, reducing competitive intensity and squeezing its pool of talent. Despite the consolidation, large firms aren’t exactly minting money. And above it all, the government seems determined to sneak in ridiculous laws that could kill what growth potential is left.

What factors will shape the future of India’s media & entertainment industry in the coming years? Here’s a breakdown.

Bigger isn’t (always) better

Even as Reliance prepares to take over Disney-Star, consider the run the last media mega-merger has had. More than a year after PVR and Inox merged, India’s biggest multiplex chain is struggling to make money. Despite a dream box office quarter last year thanks to back-to-back hits, PVR-Inox has not managed to consistently recover from the pandemic (read more in this edition of The Impression). This June quarter, PVR-Inox’s revenue fell and losses after tax (pdf) rose as fewer films hit the screens and viewers stayed busy with the elections and cricket.

This isn’t a one-off. As I explained in previous editions, exhibitors and film producers are locked in a downward spiral of risk-averse behaviour. That has left cinemas with long lull periods of few films while producers stake everything on extremely high budget projects, rather than releasing many lower-budget films.

Meanwhile, consolidation among streaming platforms has already caused dramatic shifts in the business of web-series and other content. Amazon bought MX Player from Times Internet, Saregama acquired Pocket Aces last year, while Hotstar and Jio Cinema will soon be sister concerns. Streaming industry insiders tell me there is a marked slowdown in the number of projects being commissioned at all major streaming platforms. Some, like Zee5, had stopped taking meetings for new ideas entirely, although they have now resumed scouting for new projects somewhat. Others, like Hotstar, are also going slow and focusing more on “TV+” content, meaning web-shows with lower budgets and many more episodes, much more like Indian TV shows than high-quality originals.

There is more work to do for platforms such as Amazon miniTV and (now) MX Player, but they typically look for lower budget “TV+” type content as well, since their business model is primarily ads, not subscriptions. For those wishing to make top-shelf content, the balance of power has shifted more decisively in favour of (primarily) Netflix and Amazon Prime Video. As one industry insider told The Impression: “you can either go back to doing TV, or try your luck breaking into films, or wait around for Netflix or Amazon, maybe Sony or Hotstar to greenlight your project. But they have plenty of choices.”

In total, the drop in demand for high-budget streaming originals will have an impact on the production houses and independent creators that made significant money in the last seven years of the streaming boom. As of FY23, streaming success stories such as TVF and Applause Entertainment were already working on thin margins.

Yet, the consolidation juggernaut will probably not cease. Sony is still looking to acquire a rival media business after its aborted merger with Zee Entertainment. In the news business, newly interested parties are putting together funds. Adani Group’s media arm AMG Media received Rs 900 crore from its parent firm in FY24, after acquiring legacy news brands NDTV and IANS. That’s much more cash than what it spent on both acquisitions.

Damocles’ Sword

Nothing kills the media business faster than curbs on free speech. The Indian government does not seem to understand this or is perhaps unwilling to let any medium that allows its critics to thrive run without interference.

The insecurity shows in the government’s efforts around the Draft Broadcasting Services (Regulation) Bill, 2024. First, the ministry of information & broadcasting has circulated copies of the draft to a select set of stakeholders rather than opening it to public scrutiny, as is standard for all proposed legislation. What’s more, it seems the MIB marked each copy with a unique watermark so that if one is leaked to the public, it can track the source. That’s a lot of corporate crisis management strategy for what is merely a piece of legislation meant to update a cable TV law from the 1990s.

What is the government so nervous about? As Aditi Agrawal of Hindustan Times reported over the last few weeks, this draft proposes opaque and sweeping clauses that will stifle digital media altogether.

Two major provisions are of particular concern.

First, the draft stipulates that all platforms and individual ‘broadcasters’ will have to form a content evaluation committee, start a self-regulatory organisation, and appoint a grievance redressal officer for any complaints by any viewer of their content. This onerous compliance won’t just apply to massive multinationals like Netflix and Amazon but could also fall on smaller, independent creators such as, say, YouTube channels and Substack writers.

Second, Hindustan Times reports the current draft of the bill has proposed that “news influencers” will also be considered “individual broadcasters” and brought under this law. However, the definition of a ‘news influencer’ is so vague, it could include anyone on any internet platform who comments on current affairs or provides knowledge, including podcasters, Twitter accounts, or Instagram curators of the news.

Influencers like Ranveer Allahabadia and Kamya Jani, who often run interviews with political and business leaders and comment on public affairs could also be forced to appoint grievance redressal officers for their YouTube channels. Will this also apply to creators like Dhruv Rathee, who lives in Germany but creates for a Hindi speaking audience? How about Mr. Beast or Marques Brownlee, foreign creators with a large fan base in India? Without a public discussion these questions remain unanswered. It’s unclear if the authors of this draft have even considered the impact of their proposals on the way the internet works in 2024.

What is certain is that if laws like these are passed, India’s media and entertainment business will be at the mercy of unprecedented levels of censorship. Besides, it is exceedingly difficult to monitor every corner of the internet effectively; it’s more likely that the thin-skinned authorities will use these laws to target creators and businesses they have a problem with, especially anti-establishment voices in both news and entertainment.

Those in the business are extremely unhappy with this draft. Although the government is doing its best to keep it from discussions, RTI queries revealed industry bodies and civic society groups have criticised the legislation for poor understanding of how content creators on the internet should be regulated.

A fearful, chaotic environment isn’t great for an already difficult business. Our vast population and rich cultural legacy mean India can make its media business its number one export, just like South Korea has done. But how long before Big Tech firms and international media companies decide India just isn’t worth the investment?

Last Scroll Down📲

Scan the big media headlines from the week gone by

Looking up: Listed Indian TV broadcasters had a better than usual June 2024 quarter, with a big jump in revenues due to growth in ads during this year’s prolonged election season.

It’s vintage: Fintech firm Infibeam has acquired Rediff, one of India’s earliest digital news and content companies, for Rs 25 crore; Rediff was founded in 1996 by veteran ad executive Ajit Balakrishnan.

Rebound: Social media firm Reddit Inc reported better than expected results, with revenues up 54% year on year led by growth in ad revenue and a massive jump in ‘other income’ including data licensing deals with platforms such as OpenAI.

Meta has also forecasted better-than-expected growth in its quarterly revenues.

Drops: Meanwhile, British advertising Big Four agency WPP downgraded its growth estimates for the year, expecting a decline in its China and domestic businesses to outweigh the growth from Europe, US, and India.

Trumpet 🎺

Dissecting this week’s viral ‘thing’

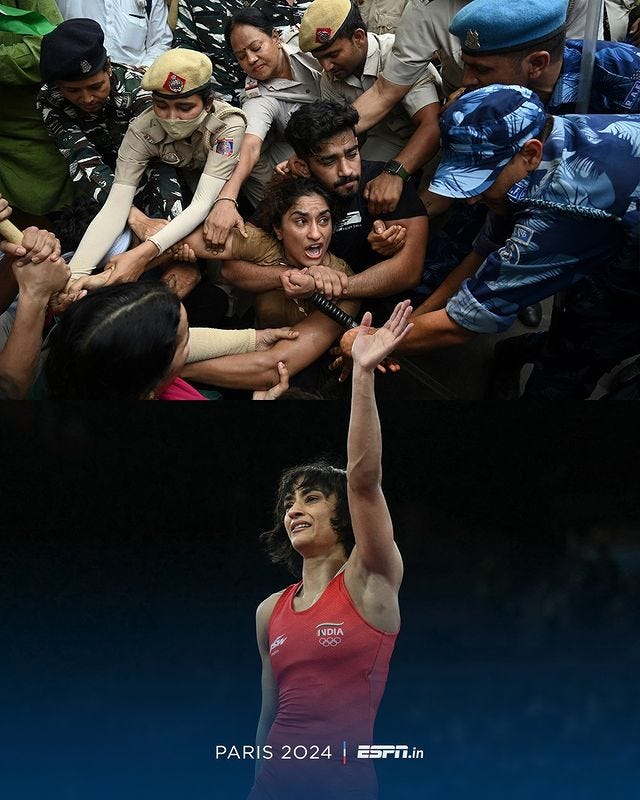

Sports news websites aren’t likely to be flag-bearers of anti-establishment sentiment, or any political resistance at all for that matter. But some victories are borne out of so much pain, that even ESPN cannot help but contextualise them.

This composite, going viral on almost all Indian social media, depicts wrestler Vinesh Phogat after her unbelievable win in the 50 kg women’s wrestling semifinals at the Paris Olympics. Phogat is now the first ever Indian woman to make it to wrestling finals in the Olympics; she beat an undefeated Japanese wrestling champion Yui Susaki. She is coming home with at least a silver medal (although latest reports suggest she may be disqualified for being slightly overweight, heartbreaking).

She will also come home a symbol of resistance against India’s abusive political establishment. Phogat and other female Indian wrestlers have been leading a protest against BJP leader Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh, the former president of the Wrestling Federation of India. He is accused of sexually exploiting several female wrestlers during his tenure at the WFI; you may remember that just last year, several protesting wrestlers including Vinesh Phogat were forcibly dragged away by the police from where they were protesting.

Phogat, Sakshi Malik, and other protesting wrestlers have been at the receiving end of a vitriolic media campaign ever since. It started with this AI-manipulated photo of the wrestlers, purportedly smiling after being detained by the police. Then, top anchors at India’s leading news channels ran primetime narratives discrediting not just the wrestlers’ protests but also their sporting careers.

We will probably be treated to a completely different narrative from the nation-loving media once the Olympics are over and Phogat brings home a medal, making India proud. The government may release a video of Prime Minister Modi congratulating Phogat on the phone, as he has done with other Indian winners this season. There are already memes about the PM preparing himself to make the call.

Phogat probably won’t care though. Fellow wrestler (and protestor) Bajrang Punia told ESPN that Phogat promised to win gold in her last ever Olympics not for her career, but to “fight for the young women wrestlers who will come…so they can wrestle safely.”

All the best, Soumya!

Part of the journey is the end!

Upwards and onwards, Soumya... eagerly awaiting your next big adventure!