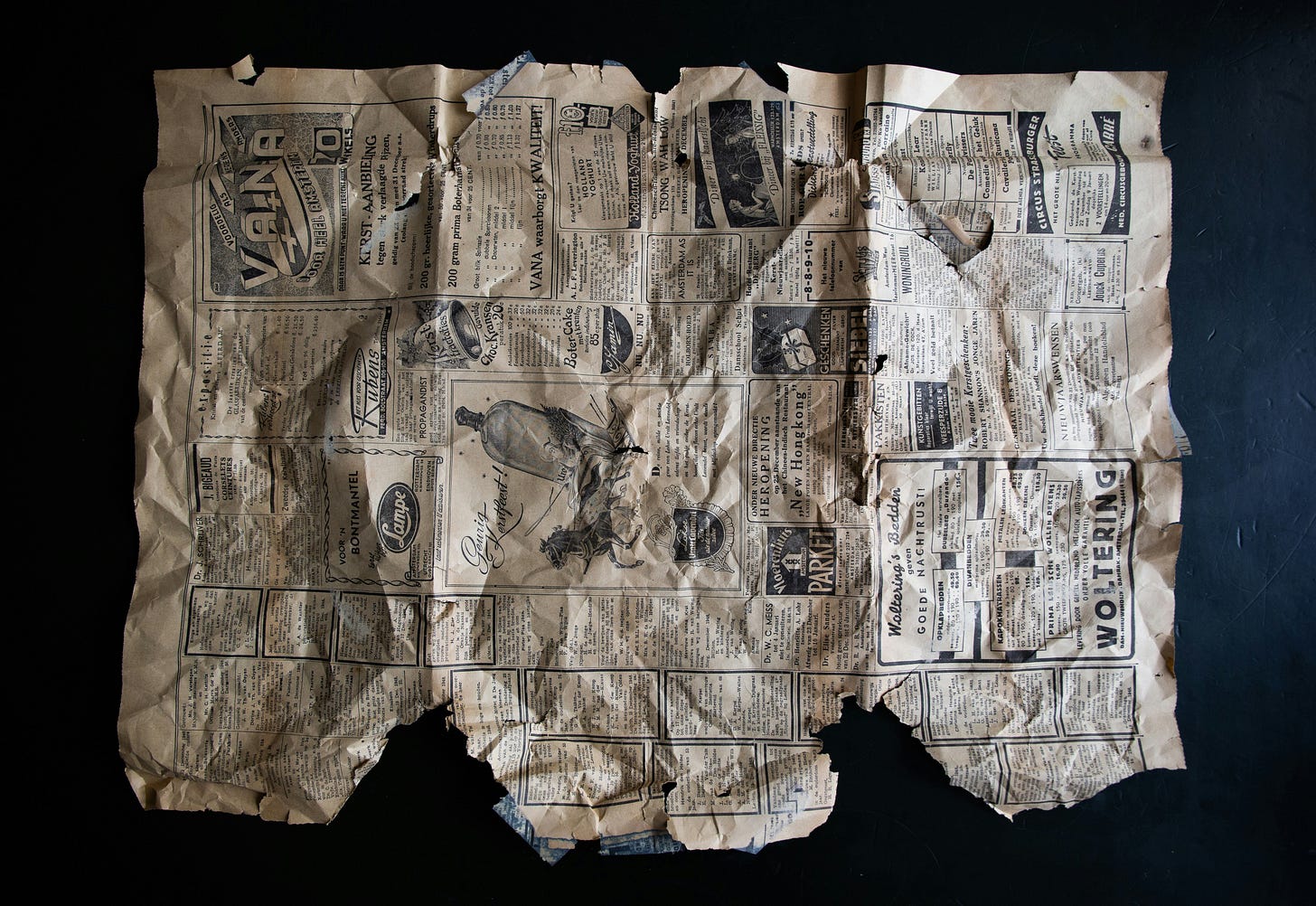

News Is Broke(n). Now What?

Journalists around the world are losing their jobs. Why are newsrooms unable to make money?

Good afternoon!

Welcome to The Impression, your weekly primer on the business of media, entertainment, and content.

If someone shared this newsletter with you or if you’ve found the online version, hit the button below to subscribe now—it’s free! You can unsubscribe anytime.

I have a confession to make: this is not a good time to be a journalist. Over the last few months, newsrooms in North America, Europe, India, and other major markets have laid off thousands of employees. In the US alone, Poynter estimates more than 2,600 jobs were affected in just 2023, more than the cuts from the previous two years combined. Globally, this number may be at least 8,000, per UK media business portal Press Gazette.

We’re only a month into 2024 but the layoffs aren’t abating. This week, UK’s public broadcaster Channel 4 announced it will slash 240 jobs, its biggest cut in over 15 years. Earlier this month, the iconic sports magazine Sports Illustrated laid off almost all of its staff after parent firm The Arena Group lost its licence to publish the magazine. The magazine’s union is now suing the company for what it alleges was ‘union busting’, not a cost-cutting exercise. And last year, the Times Group, among India’s top five media conglomerates, laid off 120 people from its digital vertical; a week later, it let go of 30% of the team from ET Prime, the digital subscription-only arm of Times Group’s The Economic Times.

Like I said, it’s a bad time to be a journalist.

But this isn’t new. The business of news has been struggling for a long time. ̛It has claimed high-profile casualties including BuzzFeed, Vice, and The Huffington Post.

The bigger question is…

Can the news make money?

Chitranshu Tewari prefaces his answers with a disclaimer: “I’ve never worked with legacy media.” He’s the director of product and revenue at Newslaundry, a subscription-driven news company. Tewari is responsible for growing Newslaundry’s subscription business and setting up its award-winning app, along with an events business. Newslaundry has been for-subscription since its inception as a media critique platform in 2012.

“If we wanted to give readers an alternative, then we couldn’t run our shop the way legacy media does,” Tewari told The Impression. ‘Today legacy media is coming to the realisation that it should do niche content, publish only eight pieces a day, that longform stories and videos and podcasts work. We knew this from day one.”

Tewari brings up a singular problem affecting almost all ad-driven businesses around the world for years: all the ad money online is going to Google, Meta, and now increasingly, Amazon. Publishers, such as those who produce news, are left with a much smaller share of the pie every year. “Everyone wanted to offer free content [on social media platforms] so that the feed gets updated,” he says. “Then platforms figured out that from a policy, content, and misinformation standpoint, it isn’t worth it. But this whole journey took them 6-7 years.”

The numbers tell the story.

A survey in the latest EY Media & Entertainment report 2023 (pdf) found that 80% respondents said they consumed news daily on social media, far more than via websites, apps, TV, or print. Of the total hours spent online in 2022, barely 1% was dedicated to news and information. An overwhelming majority of people are engrossed in social media and scrolling through video. In general, people are consuming and sharing less news than before and prefer listening to influencers and celebrities talk about the news rather than journalists and newsrooms.

Times Group is by far the largest online news platform (among news companies) with over 350 million unique visitors a year per the EY report quoted above; Zee News and Network18 came in a distant second and third.

Yet, ad revenues have remained elusive for all three.

Take Times Group for instance. In FY20, Bennett Coleman & Company Ltd made over ₹5,300 crore (~$650 million) in ad money from all its media operations and subsidiaries. Then Covid hit, and ad spending contracted worldwide.

In India, it dropped by over 21%. But globally, Meta reported a strong 21% growth in ad sales in the pandemic-struck year while Google’s parent Alphabet came in at a modest 8%. That year, digital ad spends in the US grew 12% despite an initial pullback in the panic of lockdown measures.

But while digital advertising leaders Google and Meta have recovered from the slowdown, the Times Group could not get back to its pre-pandemic trajectory. Group ad revenue nearly halved in FY21, then began to grow again rapidly but still only made it to a shade over ₹4,900 crore ($600 million) in FY23, the latest available data for the company. And now, the company is reportedly splitting, with brothers Samir and Vineet Jain carving out news, TV, radio, and other entertainment assets between themselves. Bereft of other ad assets to hedge its bets, the Times Group’s news business must now fend off competition from the Google-Meta advertising duopoly on its own.

Meanwhile, advertising revenue for TV18 (comprising news along with entertainment under Viacom18) has grown through the pandemic years but stagnated in FY23 at ₹5,244 crore (~$630 million) as per the company’s annual report (pdf). Most of the ad sales growth came from the entertainment business and not news, whose operating revenue declined 1% in FY23 (pdf). Besides, TV18 and Moneycontrol, the company’s digital business news platform, will now merge with parent firm Network18 as Reliance prepares to acquire Disney’s India assets.

Finally, there is Zee Media, home of Zee News, DNA, and other legacy news brands. Although the company’s growth faltered in FY20, revenue from operations recovered to reach a peak of ₹866.8 crore (~$104 million). Then, in FY23 (pdf), it fell nearly 17% and the company slipped into losses. More than 90% of Zee Media’s revenue comes from advertising.

Compared to Meta India and Google India’s ad sales, these numbers are puny. What’s more, Meta’s ad sales in India grew 13% in FY23 to over ₹18,000 crore (~$2.17 billion) while Google India’s ad sales were up 12.49% to over ₹28,000 crore (~$3.37 billion). All this, while TV consumption is on a slow decline (read more about it in this edition of The Impression).

Will you pay for news?

Clearly, news publishers are unlikely to ever bridge the massive lead that Google and Meta have in digital advertising. Where does that leave us?

The current Hail Mary pass for legacy media is subscriptions. After all, putting stories behind paywall has boosted the fortunes of their foreign counterparts. In November, The New York Times crossed 10 million subscribers as revenue grew over 9% and profits by over 30% (more on this later). In India, Newslaundry is among the earliest in India to adopt the subscription model. But Newslaundry also reported a 6.5% decline in revenue from operations in FY23 to ₹5.06 crore (~$610,000) and slipped into a tiny loss.

Still, Tewari says, it’s better to stick to subscriptions and subscriber events than run after ads that aren’t coming.

“We have been shielded a lot by the highs and lows of the news ecosystem because we are on a subscription model,” he told The Impression. “More often than not, in the news business, we are blindsided by easy money. Platforms will pay publishers who will jump on what is trending, such as short video. Publishers then don’t care about what is important to them editorially or from a business standpoint.”

But subscriptions haven’t really worked for legacy media yet. In its latest annual report, TV18 attributed the rise in subscription revenue largely to its sports and JioCinema businesses. The EY Media & Entertainment report pointed out that there were few takers for paid bundles of ad-free digital news and e-papers because the same news was available freely on the internet. “Why should I pay to an [The Indian] Express or [The] Hindu if I will get the same news in a different publication for free?” Tewari asks.

Even getting billionaires to fund news publications with patient capital hasn’t paid off. Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and Time magazine are all losing money as both ads and subscriptions decline after rapidly growing during the pandemic. Rivals like The New York Times are holding strong as they lure subscribers with more than just news: they’re selling games, recipes, and gadget reviews bundled with the news. But as Tewari puts it, that strategy only works if non-news offerings are crafted carefully to appeal to the premium audience that subscribes to the news.

Sometimes, newsrooms fall victim to inexplicable battles. The LA Times’ executive editor Kevin Merida reportedly quit his job after the paper’s owner Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong asked him to kill a story involving a wealthy doctor friend whose dog had allegedly bitten a woman.

Meanwhile, energy drink billionaire Manoj Bhargava acquired Sports Illustrated publisher Arena Group in what seems like a hostile takeover even though his firm was already in the process of merging with the publisher. Bhargava then promptly began firing top Arena executives.

Back home, the Adani Group bought news wire service IANS at the ridiculously low price of ₹5 lakh or around $6,000 (read more in this edition of The Impression). Adani also revived the erstwhile business news channel NDTV Profit, rebranding its acquisition BQ Prime and using NDTV’s TV licence.

Perhaps the answer is that the news cannot be a for-profit enterprise. In a note in his newsletter Outliers, journalist Pankaj Mishra argued that the true future of journalism lay in “slow, deep, nonprofit, and human-centric model”, much like his venture FactorDaily that became a nonprofit media lab in 2019. That would demand rethinking the role of news distribution and journalists altogether. After all, since ancient times, news was meant to be a government-run public service. Or, as Don D Patterson describes in his book The Journalism of China (pdf) the earliest reporters were simply the town’s busybodies gathering news and gossip during the day to relay it in evening gatherings at teahouses.

Last Scroll Down📲

Scan the big media headlines from the week gone by

Upgrade? No, thanks: Streaming’s subscription era may be truly over. A survey found less than 10% of Amazon Prime members in the US were willing to pay an additional $2.99/month to watch Prime Video ads-free. Amazon introduced ads to the basic Prime Video subscription this week. Some US users plan to cancel their subscription altogether, saying ads in a streaming service they paid for is unfair.

Also, The New York Times has a list on what Americans streamed the most in 2023 amidst the Hollywood strikes. Hint: they binged on classic TV.

Eat your words: Zee founder Subhash Chandra told both The Economic Times and Mint that he will sue Sony for deliberating scuttling their $10 billion merger. He also promised to hike the family’s stake in Zee without raising money from outside. Now, market regulator Sebi is reportedly examining Chandra’s statements for potential breach of disclosure norms, although Zee has denied this. Remember: Sebi is already investigating various members of the Goenka family for financial fraud.

Please don’t stop the music: Universal Music is refusing to renew its music licensing deal with TikTok. In a letter to musicians and artists, the world’s biggest music label said the social media platform was offering a bad deal to artists and removing tracks from up-and-coming artists represented by Universal as an intimidating tactic. Without a deal, TikTok will lose rights to the music of Taylor Swift, Drake, and Eminem among others.

It’s paying off: Gaming is now officially Microsoft’s third largest business, ahead of Windows and the ads business, courtesy the company’s acquisition of Activision Blizzard. Gaming revenue was up 49% year on year in the December 2023 quarter (pdf). Despite the growth, Microsoft is already cutting fat. Last week, it scrapped the video game Odyssey, which was under-development for six years, and cut some jobs.

Trumpet 🎺

Dissecting this week’s viral ‘thing’

Indian brands can’t seem to divorce ‘pre-buzz campaign’ from ‘straight-up misinformation’. A few months ago, I’d told you about how Freakins’ Jeans hired internet sensation Uorfi Javed for a marketing campaign involving a couple of women impersonating the Mumbai Police and ‘arresting’ Javed for obscenity. Spoiler alert: Mumbai Police sued everyone involved. It’s illegal to pretend to be the police.

This week, we were treated to at least two more instances of misinformation masquerading as pre-buzz marketing.

First, dancer and actor Nora Fatehi took to her Instagram stories this week to make a familiar complaint. Someone was using her deepfakes to market fake brands, including a knockoff of international luxury athleisure company Lululemon. Already, several celebrities including Rashmika Mandanna, Amitabh Bachchan, and Sachin Tendulkar have cautioned the public about their deepfakes. Turns out Fatehi’s was a case of the boy who cried wolf: the whole thing was a marketing stunt for HDFC Bank’s anti-fraud mascot Vigil Aunty. You sure got our attention. But will anyone now take an actor’s complaint about a deepfake seriously?

Second, HT Media announced it was shutting down its iconic 104 Fever FM due to “evolving trends in the media industry.” It’s totally believable: private radio channels have declined so much that they asked the government for a bailout package last year. Except… Fever FM isn’t shutting down. Turns out it may have been a gimmick to announce that the radio channel is going digital, complete with the tagline ‘purana radio ab khatam’ (old radio is over). Amid all the ongoing media layoffs and shutdowns, surely there was a better way to grab attention?

That’s all this week. If you enjoyed reading The Impression, please share it with your friends, family, and colleagues. And please write to me anytime at soumya@thesignal.co with thoughts, feedback, criticism or anything you’d like to see discussed in this space. I'd love to hear from you.

Thanks for reading, and see you again next Wednesday!