For Creators, Money is X-Rated

The pandemic-era boom in India’s ‘creator economy’ is gone. Some startups are making early profits, but their success (and rivals' struggles) bare an unsavoury truth about ‘creator economics'.

Good afternoon!

Welcome to The Impression, your weekly primer on the business of media, entertainment, and content.

If someone shared this newsletter with you or if you’ve found the online version, hit the button below to subscribe now—it’s free! You can unsubscribe anytime.

This is the story of two companies in one hyped business: the creator economy. Both companies help creators make money from connecting with their audiences directly, helping them sell everything from calls and livestreams to courses and seminars. Both were founded roughly a year apart during the pandemic, when entrepreneurs were dropping the words ‘creator’ and ‘economy’ liberally to get investors excited.

But Rigi and Renown, both based in Bengaluru, both creator monetisation apps, picked different roads to building a business. In that choice lies an inconvenient truth about the economics of the creator economy: to really make big money, you need to sell some sex. Or at least the (remote) possibility of it.

The Adult-Only Future of the Creator Economy

When Nidhi Chaudhary posts a Reel with life advice, she draws on her knowledge of astrology, tarot reading, Hindu scripture and, sometimes, the Chinese art of feng shui. She offers tips to overcome pretty much any kind of challenge in life: from finding a romantic partner to succeeding at work, dealing with stress and anxiety, and attracting all the money in the world.

Nidhi ji is extremely successful. She has more than a million followers on Instagram and YouTube combined, and hundreds of thousands more on other social media platforms. She hosted an astrology show on the TV channel India News. She also has her own website and personalised app to connect directly with her fans.

But most of the fans seem barely interested in astrology or advice. The comments section of her videos is full of (presumably) men thirsting over her looks and clothes, in particular her saree blouses that tend to leave little to the imagination. Reel after Reel is dominated by fans either criticising her for her “inappropriate” clothing or posting sexually explicit compliments.

None of this bothers Chaudhary, though.

“I don’t have to deal with comments, I don’t care about them,” she told The Impression. “Let them say, that is their karma, they will face it.” When men who pay for a private session with her happen to make inappropriate sexual requests, she politely asks them to read the Hanuman Chalisa, or go for a run every morning to get rid of ‘negative energy’.

She’s content to redirect such fans to her app, where they can pay ₹1,100 ($13.3) to ₹15,000 ($180) for private astrology consultations via text or calls. The app also lets fans subscribe for just under ₹13,000 ($156) a year to get exclusive access to photos and posts from Nidhi ji.

The Nidhi Chaudhary app is hosted on a domain called ‘my-fan.app’, owned by creator monetisation startup Renown. And where other creator economy apps are struggling to sustain after the initial hype and the funding it brought, low-profile Renown is making profits from the get-go.

Promised ‘good time’

Renown runs a family of domains on which a creator can build a custom app, no coding required. Renown was founded in 2020 by IIT-Kharagpur graduates Ravish Kumar and Aditya Barelia (who also runs an HR technology firm, Autogram). But there’s little other information on the company. Its filings with the Ministry of Corporate Affairs show it has raised money from a clutch of high-profile investors, including Rajesh Yabaji (founder of logistics startup Blackbuck) and Sequoia Capital’s Seed (Sprout Investments II), a fund focused on early-stage companies.

Apart from my-fan. app, Renown also offers several other domains such as join-my. app, and myinfluencer. app. It earns by taking a share of the creators’ revenue. Renown’s website doesn’t have an official list of creators it serves, and the company’s founders did not reply to my requests for comments.

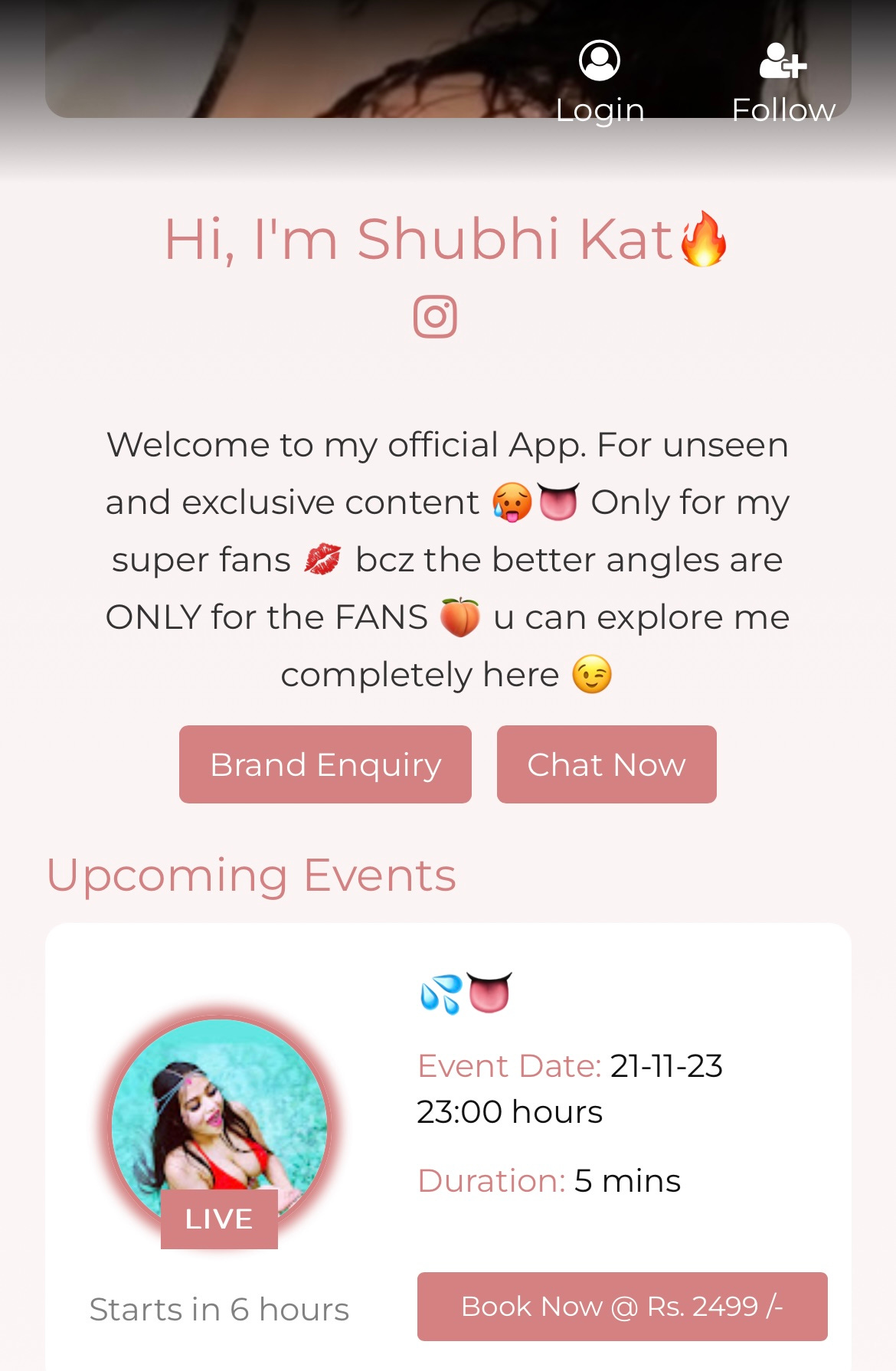

A search through Instagram reveals several models, actresses, and other creators who use Renown-based apps to connect with their fans directly, largely via one-on-one calls and video sessions. In fact, with an app in place, there are endless opportunities for monetisation; I found creators on Instagram using their (Renown-based) apps to sell everything from a 15-minute audio call for ₹1,899 ($23) to their “used products” for ₹8,000 ($96) each, personalised videos, and packages to “date” the creator for a day or take them out on a long drive for thousands, even lakhs of rupees.

Renown isn’t the only company offering this; Jaipur-based Celebgaze Media also allows creators to make their own apps. The company operates apps for a long list of creators, largely women, who offer health, lifestyle, and fashion content, with more tips and webinars available via their personalised apps. Several creators also offer “exclusive” or “sexy” pictures, videos, and livestreams to subscribers of their apps.

There are plenty of veiled references to OnlyFans, the UK-based creator platform best known for selling pornography to subscribers.

Follow the money

The OnlyFans reference is fitting; it is perhaps the only creator economy company making money at all. In the financial year ended November 2022, parent firm Fenix International (download pdf here) reported $1.08 billion in revenue (up 16% year-on-year) and a hefty 37% net profit margin.

Renown, too, is making a profit right from when it started, a remarkable achievement for a creator economy company. In FY22, it made ₹12 crore (~$1.44 million) in revenue and a modest profit of ₹28 lakh (~$33,600). It was profitable in FY21 as well, its first full year of operations.

By contrast, more well-known creator monetisation platforms have been struggling to make money. FrontRow, backed by big VCs such as Elevation Capital and Lightspeed Venture Partners, shut down earlier this year. The company offered classes and seminars with celebrities and popular artists, including writers, comedians, and musicians. Several more have shut shop in the last year, many backed by deep pockets including Matrix Partners and Titan Capital.

Rigi has raised $25 million from VC firms Stellaris Venture Partners and Accel India, and cricketer Mahendra Singh Dhoni. The company, founded in 2021 by BITS Pilani graduates Swapnil Saurav and Ananya Singhal, allows creators to offer classes and webinars on its app. It hasn’t turned a profit yet. Company filings show that in FY22, it made ₹18 lakh (~$21,600) in revenue and ₹3.45 crore (~$410,000) in losses.

But Rigi steered clear of the kinds of creators that Renown and Celebgaze have embraced.

“The most lucrative category in the creator economy is borderline for-adults content,” co-founder and COO Singhal told The Impression. “But we don’t make a product that we can’t tell our parents about—that’s our moral compass. Why do you want to go anywhere near the borderline? This is a dicey proposition, and the laws of the land make it even more risky. We want to build a scalable business, not one where the police comes knocking at my door tomorrow.”

Instead, the company focused on other lucrative creator categories, such as finfluencers. Their financial advice and investment strategy seminars also exploded during the pandemic, more so when India’s markets went on a dream bull run in 2021. But the business has been suffering ever since India’s markets regulator Sebi began cracking down on finfluencers who aren’t licensed.

This year, Sebi has imposed fines worth crores on both prominent finfluencers (see this edition of The Impression) as well as relatively unknown YouTube channels involved in pump-and-dump schemes. A lot of investment advice is now handed out on private Telegram groups rather than well-publicised platforms.

Inconvenient truths

Now that the frenzy around the creator economy is finally waning, it’s time for a reality check.

First, the majority of creator economy funding at its peak in 2021 went to creator discovery platforms, and only a fraction to creator monetisation tools such as Rigi and Renown, as per data from VC firm Kalaari Capital (pdf). Discovery platforms include short-video apps and other homegrown social media platforms competing with Big Tech firms, such as Sharechat, Moj (video), and Pratilipi (audio). Forget monetisation, many of these discovery platforms are struggling to make money; just this week, Sharechat reported a 38% increase in losses for FY23 to over ₹4,000 crore (~$480 million), nearly four times its total income for the year.

Second, creators aren’t making most of their money from monetisation. Brand deals—sponsored social media posts and other branded content—are far more lucrative for all kinds of creators. Per the Kalaari Capital report quoted above, 77% of creators depended on brand deals for their income in 2021. What’s more, India had only 150,000 professional creators (with over one million followers) that year, and only 1% of them could potentially earn more than $2,500 a month, Kalaari Capital estimated.

Even today, creators prefer brand deals over dealing with individual fans clamouring for their attention. “For monetisation, brand deals are the best; most of my income comes from them,” astrologer Nidhi Chaudhary told The Impression. “It’s difficult to connect with so many clients to make the same amount of money. I’ve been turning away astrology clients lately, even though many are big businessmen and celebrities. Sometimes, you’re not in the right frame of mind to read their [tarot] cards.”

Besides, creators now have plenty of monetisation tools available on Big Tech social media platforms. In the last couple of years, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Snapchat have all introduced systems to pay creators, via subscriptions or virtual gifts. YouTube has been at it the longest. Some of India’s best-known creators are YouTubers.

Finally, the rule of making money on the internet is that when nothing else sells, sex always will. Creators making money from personal apps on Renown or Celebgaze obviously aren’t openly offering sex for money. It’s illegal in India to do so; but also, that’s not where the real appeal lies.

Creators like Nidhi Chaudhary or Prakriti Saha, a young Nepali travel, fashion, and fitness influencer, are serious about their areas of expertise and unabashed about their sex appeal. They also mercilessly troll creepy men who slut shame them in comments or ask them for sexual favours. In a deeply patriarchal and violent society, being unapologetic for being sexy in public is a subversive act. That act of resistance (and the fighting in the comments) keeps the men coming. Many of them will pay for one-on-one sessions, maybe get lucky enough to receive “hot pics”, or simply get disappointed after receiving an astrology consultation.

Retaining and engaging an audience is a creator’s biggest problem, and the key to successful monetisation. These creators have cracked a sure-shot way to keep their audience always wanting more. And that’s the only way anyone—creator, platform, big-name investor—will make good money.

Last Scroll Down📲

Scan the big media headlines from the week gone by

Suffocated: The government has proposed that TV channels, streaming platforms, and platform aggregators (such as Tata Play) set up content evaluation committees (CECs) to certify all content before its release online. The industry is worried: it’s expensive and cumbersome to set up committees, and there’s too much content to certify. Many creators will reject the process altogether. Besides, the government wants to specify who should be included in these CECs.

Already, India’s streaming industry is plagued by self-censorship as the government dangles the threat of protests and frivolous police action for anti-Hindu and obscene content.

Flopping hit machine: Superhero fatigue is real. Disney’s latest Marvel offering, The Marvels, has tanked at the box office, even as the MCU’s period of decline persists. Disney chief executive Bob Iger is now trying to clean up its movie slate, prioritising quality over quantity, and slashing budgets overall.

Franchises are doing fine in India, though. Tiger 3, the latest instalment in Yash Raj Films’ Spy Universe, has made nearly ₹300 crore (~$36 million) at the box office.

X marks the spot: Elon Musk’s online shenanigans continue to dog his newest acquisition. After Musk supported an antisemitic post on X (formerly Twitter), big brands like IBM, Apple, and Disney have pulled ads from the platform. So has Paris Hilton’s entertainment firm, which X’s CEO Linda Yaccarino had touted as a “launchpad” for experiments in video, audio, and live-commerce.

Open to misuse: This week, Tamil TV news channels ran a shocking, probably illegal news piece, alleging sexual misconduct at a Chennai pub. Their reporters and cameras hounded ordinary women enjoying the weekend at the establishment, shaming them for their clothes and for drinking.

Turns out, a drunken group of men out for vengeance orchestrated the whole thing with their friends who work at TV channels. Why? They were upset the pub denied them entry. Looks like the channels were only too happy to go along. All for a ‘juicy’ story.

Trumpet 🎺

Dissecting this week’s viral ‘thing’

From now until next year, it’s election season in India. This month, Telangana will go to the polls in a fight primarily between incumbent chief minister K Chandrashekhar Rao of the Bharat Rashtra Samithi or BRS Party (formerly TRS), the BJP, and the Congress.

Elections also mean ads. In India today, political ads by the party in power are so ubiquitous they’re hard to avoid and mostly cringeworthy. The BRS Party isn’t holding back expenses: on Meta alone, it’s officially running some 130 advertisements as of November.

Political ads are rarely impactful or innovative, especially during election season when every contender is keen to project their leader as a hero and their work during the past five years as life-changing. Most will also make a long list of impossible promises.

But with its ads in Dakkhani, spoken in Telangana’s capital Hyderabad, the BRS Party seems to have embraced the comedy-sketch format we mostly see in ads by startups and brands aimed at a younger audience.

The Instagram video linked above, for example, features a young man eager to meet his would-be fiancée, only to be accosted by her father who interrogates him instead. Right until the end, it’s hard to tell that the product being sold is a political party, and not a shiny new feature of some consumer-facing startup.

Similarly, this video attacks the opposition Congress (whose symbol is an open hand), showcasing a local leader making all the old promises to a potential voter, only to be dazzled by all the amenities already available in the area.

Tight, super-short scripts with meme-able moments have become the hallmark of Indian startup advertising. Perhaps that’s why the BRS Party chose this format while making ads for their biggest urban constituency rather than the old song-and-montage routine exhorting the party and lionising its leader. Besides, slick ads like these will appeal to young voters much more. And with about 30% of the Telangana electorate comprising those below 35 years of age, all parties will need smarter communication to get their attention.

Maybe we’ll see more fun, memorable election ads as more states and, next year, the country goes to vote. I’ll take the memes over the hate speeches and cringe ‘Dear Leader’ videos any day.

That’s all this week. If you enjoyed reading The Impression, please share it with your friends, family, and colleagues. And please write to me anytime at soumya@thesignal.co with thoughts, feedback, criticism or anything you’d like to see discussed in this space. I'd love to hear from you.

Thanks for reading, and see you again next Wednesday!