Is the Google-Meta ad duopoly over?

E-commerce ads are gaining in on Google and Meta’s dominance over Indian digital advertising. Can they stave off competition?

Good afternoon!

Welcome to The Impression, your weekly primer on the business of media, entertainment, and content.

If someone shared this newsletter with you or if you’ve found the online version, hit the button below to subscribe now—it’s free! You can unsubscribe anytime.

Have you ever sold anything online? There’s almost zero chance you did it without running ads on the internet. From the moment you set up shop, the Indian arms of two companies were set to get your business even before you got any—Meta and Google.

It’s no secret that Google and Facebook dominate digital advertising globally. In India in particular, the two have a near-duopoly on digital advertising, which is growing so rapidly that it has overtaken television, India’s largest ad medium.

But this shopping season, pay close attention to where you discover deals. Chances are brands are wooing you more on e-commerce websites than via a sponsored post on your Facebook/Instagram or in your Google searches.

Tightening the grip on digital advertising

Google and Meta’s chokehold on Indian digital advertising is in a vulnerable state.

For a while now, e-commerce platforms have been making inroads into Indian digital advertising, long dominated by Google and Facebook. That’s partly because Indian consumers’ behaviour has changed over the years. Per latest available estimates from the EY-FICCI media and entertainment report (pdf), nearly half of all online product searches in India now start on Amazon and only a third on Google. This undermines the value of Google Search ads, the oldest form of advertising on the internet. The report estimated that ₹7,000 crore (~$840 million) worth of e-commerce ads were sold in 2022, 14% of the total digital advertising pie.

Is it fair to say that the Google-Meta duopoly advertising that shaped the first two decades of the internet on its way out in India? Perhaps, but (as always) there are caveats.

Just out of reach

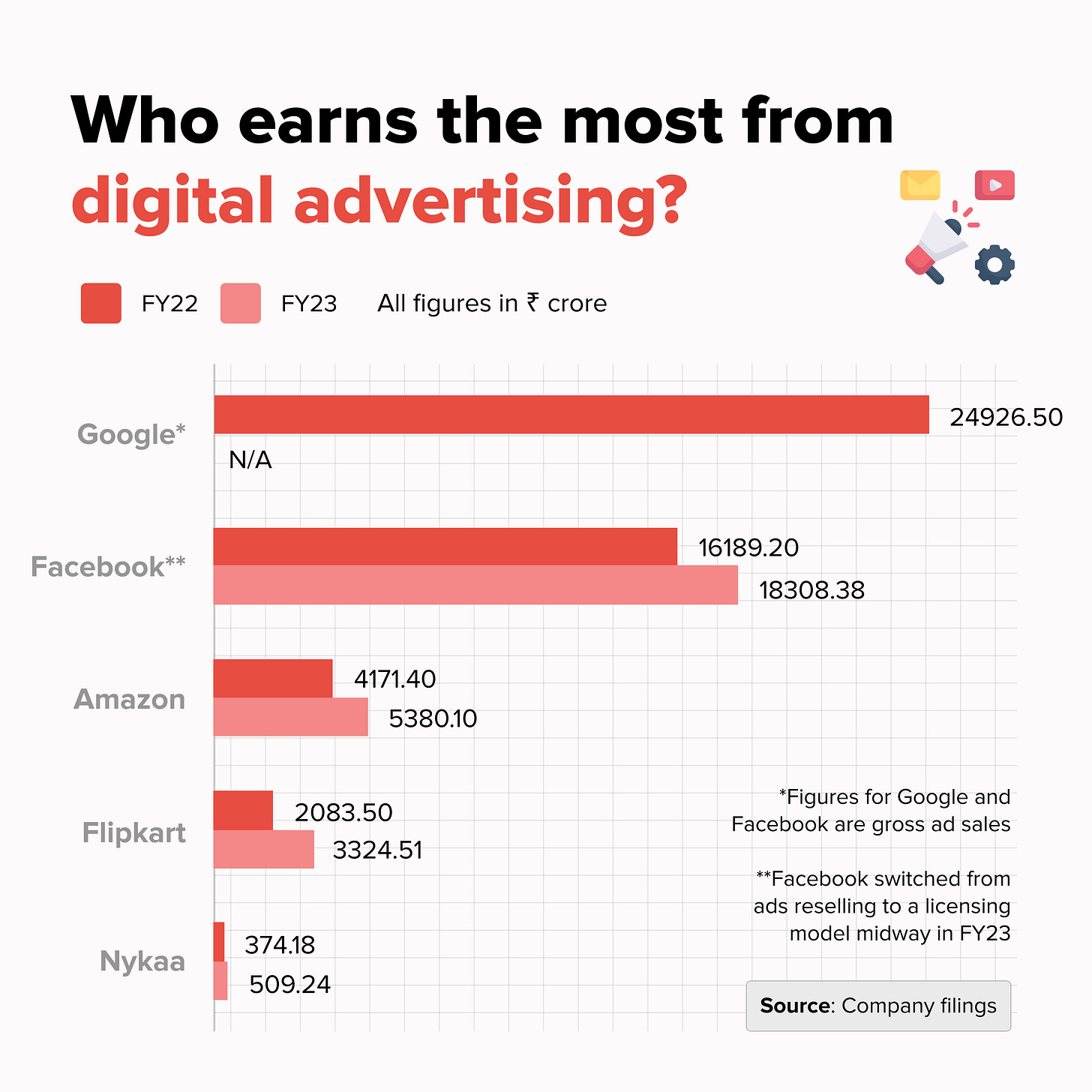

In FY22, Google and Facebook earned more from selling digital ads than Amazon, Flipkart, and Nykaa did put together. Google India is yet to file its results for FY23, but globally, its parent firm Alphabet reported (pdf) an anaemic 4% growth rate in both YouTube ad sales and Google advertising revenue for the first nine months of this year. Meanwhile Facebook India reported a 13% increase in gross ad sales for FY23, down from its usual pace of growth here.

But don’t blame Facebook and Google; this slower growth rate is in line with what’s happening worldwide and in India. Our domestic ads market is expected to grow only 12% this year, per estimates by advertising agency groupM.

Could this be the advantage e-commerce companies need to overtake their older advertising peers?

Right now, e-commerce platforms have more room to grow because their ads businesses are smaller in size. Besides, in an ads slowdown, marketing budgets tend to flow towards ‘performance’ ads which are cheaper, lower down the funnel, and geared to converting a view or click into a purchase. What better way to do that than advertise on the platform where the customer has come to shop anyway?

Both Amazon India and Nykaa posted a 30-40% increase in their ads businesses in FY23. Meanwhile, revenues of Flipkart’s ads arm jumped 59% in FY23, per Flipkart Internet’s latest filings accessed by The Impression.

Invading territory

Although Google and Meta are under siege from e-commerce advertising, they’re trying to combat it by investing in shopping ads inventory. Meanwhile, e-commerce firms are trying to build the kind of ad inventory brands go to Google and Meta for.

Take Amazon for example. Even globally, most of the ads it sells are in the form of sponsored search results, akin to Google’s classic Search ads. But it has been expanding to video on the shopping experience with a) sponsored listings that include video demos, and b) shopping livestreams. What’s more, Amazon is also selling ads aggressively on its free-to-view streaming platform called miniTV, which is available in the shopping app and now, also on the premium Amazon Prime Video streaming service. Video ads in 15-minute episode shows on miniTV aren’t just for creating brand awareness; they’re designed to redirect a user to a product listing and prompt them to buy something while they watch. miniTV’s classic pre-roll and mid-roll unskippable ads are designed to go toe-to-toe with YouTube. But while YouTube has a far bigger viewership than miniTV, the latter sits inside a shopping app, making it easier to push a customer to buy something.

Meanwhile, Meta and Google are working on ads that can bring it closer to the e-commerce experience. Now Meta has had some setbacks in building the shopping experience; earlier this year, it killed live shopping features on Instagram and removed the shopping tab from the app’s home page. But in India, it’s doubling down on catching willing customers early through WhatsApp instead of Instagram.

This year, Meta chief executive Mark Zuckerberg told investors that revenue from ‘click to message’ chats on WhatsApp in India had doubled but did not specify how much it was. WhatsApp for Business earns every time a brand texts talks to a customer on WhatsApp chats. Meta’s rates per marketing chat are among the lowest in the world, at $0.009 per text; in North American markets, the company is charging at least 2.5x the amount.

WhatsApp’s India filings show the company made ₹161.2 crore (~$19.3 million) in revenue from operations in FY23, all from the sale of marketing and customer support services sold to its American parent firm Whatsapp LLC. This was a 28% increase from the previous year; the company also made a modest ₹5.6 crore ($670,000) in profit.

But it isn’t easy to make money from a peer-to-peer messaging service. Who will use WhatsApp if their personal chats are littered with targeted ads? WhatsApp reportedly considered running ads in chats earlier this year, according to Financial Times, although the company categorically denied this. In 2020 too, The Wall Street Journal had reported Meta abandoned a plan to roll out ads in messages.

Meanwhile, Google invested in video shopping when it acquired local startup Simsim in 2021. But in March this year, it shut the company down less than two years after acquiring it. Meanwhile, its early experiments allowing creators to tag products from e-commerce websites on YouTube Shorts have remained experiments so far.

What happens now?

Google’s FY23 fillings are unlikely to show some sudden drop in ad sales, so it’s safe to assume the advertising duopoly will live to see another year. But Google and Meta are in a vulnerable position globally. They’re just about recovering from an ad spending slowdown that led to layoffs and hiring freezes, and both firms are focused on moving fast in disruptive technologies that are changing their core value proposition including Google’s AI search investments and Meta’s attempts at making the metaverse a thing.

It will be hard to stave off competition for ad dollars from e-commerce firms, particularly Amazon. In India, where social media revenues per user remain low despite a massive user base, Google and Meta will need to act fast to protect themselves from what e-commerce has to offer while trying to co-opt it.

But in the longer run, the Google-Meta duopoly isn’t just under threat from e-commerce or Amazon. Now that it’s clear that subscription businesses can’t be scaled up beyond a point, every kind of company is building an ads business. US ‘retail media’ revenues will grow to $46.4 billion this year, up 50% from two years ago. But it isn’t just retail: streaming platforms, delivery apps, airlines, even the TVs on display in an electronics store are being turned into ad inventory. As The Wall Street Journal puts it in this story, “everything is an ad network”.

Last Scroll Down📲

Scan the big media headlines from the week gone by

Oh no: Is it over? Sony and Zee have been waiting at the altar for so long, only for it all to probably fall through. Both firms are close to the finish line of their heavily delayed merger, but they have reached a sticking point: who will lead the merged entity? Zee promoter and chief executive Punit Goenka was supposed to be the man in charge, but a spate of securities fraud allegations delayed the merger, upsetting Sony. It now reportedly wants to drop him from the deal and is also unwilling to extend the merger deadline beyond December 21. With Reliance potentially buying out Disney-Star, both firms only stand to lose if the deal doesn’t go through.

The kids aren’t alright: A spate of stories this week have revealed Meta’s callous attitude towards children and their data on social media. A legal complaint revealed that Meta routinely collected data on users below 13 years old without their parents’ consent, violating US laws. Children under 13 aren’t allowed to sign up for Meta’s social media apps as per the company’s own policy. Meanwhile, an investigation by The Wall Street Journal found that Instagram’s algorithm recommends increasingly sexual content to users who follow teen and pre-teen influencers on Reels.

Election shenanigans: As multiple Indian states go to the polls, political parties and newspapers are finding creative ways to violate advertising rules. The Election Commission ordered the Congress-led Karnataka government to stop advertising welfare schemes in Telangana newspapers. Meanwhile, the Press Council of India sent notices to several papers for carrying a political ad camouflaged to look like a news headline, but did not name the offender.

Singing for the CCP: Some foreign social media influencers have found a new niche for their content—singing praises of the Chinese Communist Party. Australian think-tank ASPI found that the CCP Is cultivating these Mandarin-speaking creators—largely international students in Chinese universities—to boost its image with Chinese citizens while bashing rivals like the US. These videos follow the same pattern: anything Chinese is praised and anything deemed western is criticised.

Trumpet 🎺

Dissecting this week’s viral ‘thing’

If you’re a connoisseur of so-called ‘cringe’ Reels, you probably recognise the chorus of this song (fast forward to 1:46) that’s taken over Indian Instagram. Not sure why? This is a succinct explanation of the ‘Moye Moye’ trend that’s even got celebrities breaking out into the song during live performances.

That this Serbian song Džanum is inexplicably trending in India is interesting, but what’s more important is the implications of the song going viral here. Serbian singer Teya Dora has shot to global fame with this song on TikTok and Instagram. But that hasn’t happened in India; all that most people recognise is the ‘moje more’ of her chorus, which they’re anyway mispronouncing as ‘moye moye’. Džanum doesn’t feature in YouTube’s chart of India’s top 100 popular songs, Although, it did make a lower-ranked entry on the trending songs chart for YouTube Shorts, a short video competitor to Instagram.

What does this tell us about marketing songs on short video apps? Music labels today all aim for one thing: get their song to go viral, hopefully with a dance ‘hook step’ or a trend set to the song’s chorus. But that may not automatically result in success for the entire song or its artist. If you’re lucky, you could build a career off of songs that trend on Reels, such as singer-composer Yashraj Mukhate. If not, you may be forgotten as that one singer of that one song everybody once made really funny Reels to.

That’s all this week. If you enjoyed reading The Impression, please share it with your friends, family, and colleagues. And please write to me anytime at soumya@thesignal.co with thoughts, feedback, criticism or anything you’d like to see discussed in this space. I'd love to hear from you.

Thanks for reading, and see you again next Wednesday!