Event Trading’s Yes/No Future

They insist they aren’t real money gaming, but Indian event trading apps are being taxed like they are. Will this hurt their fight for Sebi recognition?

Good afternoon!

Welcome to The Impression, your weekly primer on the business of media, entertainment, and content.

If someone shared this newsletter with you or if you’ve found the online version, hit the button below to subscribe now—it’s free! You can unsubscribe anytime.

2023 was not a good year to be a real money gaming company. In October, the government imposed 28% GST on operators of online poker, rummy, and other online games involving actual cash. Investor interest began to wane, smaller firms put themselves up for sale, and those that have survived are expanding to foreign markets with lower tax rates. Industry representatives have challenged the tax hike in the Supreme Court and are hoping to get their first hearing in the next two months. But tax tussles take time and many fledgling gaming startups don’t have that luxury.

But while real money gaming figures out its future under a new tax regime, a much smaller, practically nascent industry is looking at an uncertain future: event trading.

Event-Trading Edges Towards Its Event Horizon

But wait: what is event trading?

Founded in the pandemic era, event-trading (also called opinion trading or prediction marketplace) platforms such as Probo, Better Opinions (now Tube11), and TradeX straddle the line between trading and real-money gaming. The game (or trade) is simple — bet on the outcome of a Yes/No question and trade opinions based on your domain knowledge or expertise of a subject matter. As more bets or ‘trades’ pour in for a given question, odds between the Yes/No outcomes keep changing. Once the actual event occurs, these odds determine how much money a player wins or loses.

Questions on event trading apps span sports, film, current events and other forms of entertainment. These could range from the specific outcome of a cricket match (Will XYZ cricket team score more than 88 runs in its first innings?) to the growth of a YouTube star (will ABC creator cross 5 lakh subscribers?) to the outcome of an ongoing news event (will companies A and B finish merging by this financial year). However, industry sources say, the majority of user activity is focused on sports, particularly cricket.

Event trading apps operate in a legal grey space in India, although they insist they are a game of skill, not chance, because users are placing bets on informed opinions rather than random outcomes of chance. The entire business model draws inspiration from Y-Combinator-backed Kalshi, an American event trading platform founded in 2019 that is legally recognised as a securities exchange. A Yes/No question on Kalshi is an ‘events contract’ as per regulations laid down by the US’ Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), meaning they operate much the same way as other derivatives such as futures and options.

Firms like Probo, Better Opinions, and TradeX had set up shop in India in the hope of building a robust business model and eventually convincing Sebi to recognise them as exchanges for a new asset class.

Instead, these firms are continuing to operate in a legal twilight zone while facing the same onerous tax structure as their real money gaming cousins.

A senior executive at an event-trading company complained that the fledgling startups were now paying the highest GST tax slab on deposits made by players rather than on their revenue, hurting their balance sheet. “Suppose a player deposits ₹100 in the morning to trade on an event,” the senior executive told The Impression, requesting anonymity as discussions on taxation rules are considered sensitive. “As a platform, I have already paid ₹28 to the government as tax. Now, at the end of the day, this player loses some money, gets bored, and withdraws the remaining ₹80 from his account. I have made a fraction of the balance ₹20 but I have already paid much more than that in taxes. Where is the justice in that?”

The problem is not new; it’s well documented in the case of online poker and rummy platforms operating in India who have also been demanding GST on their revenue instead of the entire pot. Event trading companies say they’ve been dealt a heavier blow because the government does not recognise event trading as a separate business model.

Money come, money go

Company filings show FY23 was a good year for India’s top event trading firm Probo and Better Opinions. Probo, backed by top investors, including Peak XV (formerly Sequoia India), Elevation Capital, and Nandan Nilekani-led Fundamentum Partnership, saw a 32x jump in total revenue to ₹93.8 crore (~$11.29 million). It also managed a tiny 4% net profit margin for the year. Almost all of its money was made from platform fees, charged on every trade a user makes on the Probo platform. Rival Better Opinions, backed by Y-Combinator, Meta, and other investors, had a similar jump in total revenue to just under ₹2 crore (~$240,000) in FY23 but made over ₹10 crore (~$1.2 million) in net losses. It also set up a parent firm in the US and renamed its app in India to Tube11.

Industry executives say the higher GST will likely eat into these companies’ bottomline. The lack of legal status means they aren’t able to crack other lines of business either. Take Probo, for instance. The company first diversified into new lines of business by signing deals with news and sports publishers. Under these agreements, Probo would affix its widget to these publishers’ websites where readers could trade opinions on a news item they had just read. Probo would earn from the trading readers and pay publishers a lump sum amount for access to their audience.

Those deals fizzled out because media publishers couldn’t include what were essentially real money gaming widgets on their apps, industry executives told The Impression requesting anonymity. For now, real money gaming apps aren’t allowed on Google Play Store and Apple’s App Store although these restrictions are now easing up.

Endgame: out of sight

Creating a new media & entertainment category and then securing regulatory recognition for it all while building a profitable business is arduous. But now the companies must first reinforce their business models under a new tax regime while they wait for concessions from the Supreme Court. That weakens their case with Sebi to consider ‘event trading’ market as something distinct from real money gaming.

In the US, Kalshi is fighting CFTC for barring the firm from processing event contracts linked to outcomes of the ongoing US presidential elections. Kalshi has accused the regulator of overreach, arguing none of its contracts violate the law.

India is gearing up for several elections this year as well, but event trading firms will have to remain cautious as they tread the line between being another real money game and a yet-unclassified form of online entertainment. As the senior industry executive quoted above said: “Kalshi is suing the regulator in the US, and here we are not even talking to Sebi yet.” Will India ever have its own event trading or predictions market? For now, the shadow of real money gaming is making it hard to convince the regulator.

Last Scroll Down📲

Scan the big media headlines from the week gone by

Suffering from success: Last year’s breakout (and controversial) hit film Animal is already the centre of a legal dispute. Production house Cine 1 Studios has sued its Animal co-producer T-Series alleging it has yet to be paid its share of the film’s IP rights. Cine 1 is demanding a stay on Animal’s anticipated Netflix debut until its dues are cleared. Meanwhile, T-Series says Cine 1 has no legal stake in the film.

Bump up, cut down: The advertising cash register is still ringing. Google India reported a nearly 13% increase in gross ad revenue for the year ended March 2023. It made over ₹28,000 crore (~$3.37 billion) in ad sales, more than 1.5x Meta India’s earnings, making it India’s biggest digital advertising business. But there’s trouble ahead: Google is laying off hundreds from its ad sales teams.

When the music stops: The slowdown is coming for the labels too. Universal Music, the world’s biggest label, is preparing to cut hundreds of jobs as money from streaming slows down. But chief executive Lucian Grainge is batting for a new, more sustainable royalties model and a crackdown on ‘noise’ generated by AI (read Grainge’s full memo here). Meanwhile, ByteDance’s music streaming app Resso is shutting shop in India.

Fist fight: In the latest instalment of the Disney-Peltz saga, The Walt Disney Company formally rejected activist investor Nelson Peltz’s nominees for the company’s board of directors. What’s more, it put out a snarky proxy filing, accusing Peltz of being interested in little else than a board seat, being unable to present “a single strategic idea” for Disney’s future, and being “oblivious” to ongoing changes in the media industry. Phew.

Wait for it: The Bombay High Court has been sitting on a batch of petitions challenging an IT Rules amendment that allows the government to set up its own ‘fact check unit’. This week, the HC deferred its verdict on the case once again; the hearing concluded in September. The government of Tamil Nadu also set up a similar unit; legal experts pointed out that the set-up is unconstitutional.

Trumpet 🎺

Dissecting this week’s viral ‘thing’

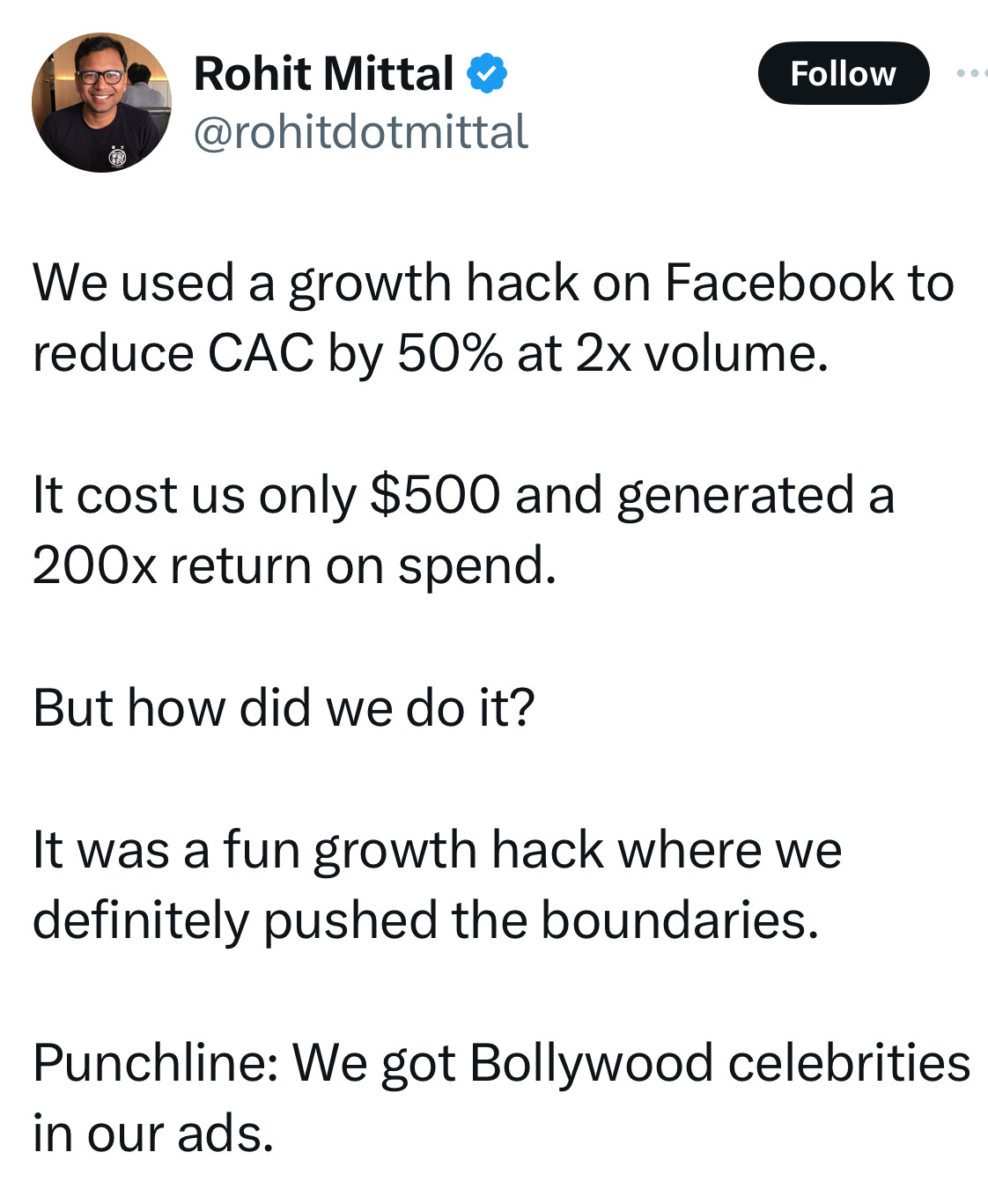

It’s really hard to find a useful growth hack in the wasteland of spammy LinkedIn posts and pompous techbro Tweets. But when you do stumble upon one, it’s always worth asking if the tip is too good to be true. Like this one from Rohit Mittal, founder of US-based fintech firm Stilt Inc. Mittal took to Twitter/X this week to explain how his team earned a 200x return on a mere $500 investment in digital ads for Stilt. His hack: use Cameo-like apps to get a celebrity to record a message for their team or customer, then use it to run ads on Facebook. Stilt bought celebrity endorsements at a fraction of the cost.

The hack really is quite ingenious. Just one problem though: it’s probably illegal.

Several users pointed out that you cannot use a celebrity’s video wishing you personally to run ads for your company, especially not without their consent. Platforms like Cameo in the US and TrueFan in India prohibit customers from recycling celebrity wishes for commercial purposes but perhaps the team at Stilt didn’t read the terms and conditions closely. Nevertheless, Stilt’s growth hack may have made its way back to some of the celebrities involved (such as actress Kalki Koechlin and badminton star Saina Nehwal) because Mittal seems to have deleted his post.

Celebrities will need bigger, better legal representation in future because it’s getting very easy to misuse their likeness for ads. Just this week, cricket legend Sachin Tendulkar warned followers that a mobile game called Skyward Aviator Quest was running ads using AI-generated deepfakes of him.

Now, to an informed user, Tendulkar’s deepfake and Koechlin’s misused video are obvious scams. Will these eventually stop working on regular folks too?

That’s all this week. If you enjoyed reading The Impression, please share it with your friends, family, and colleagues. And please write to me anytime at soumya@thesignal.co with thoughts, feedback, criticism or anything you’d like to see discussed in this space. I'd love to hear from you.

Thanks for reading, and see you again next Wednesday!